If it takes a village to raise a child, then it takes a whole team of incredible people to raise a PhD. I began this journey in August 2017, as a first-generation undergraduate with little idea of how to actually navigate grad school. Some of the many things I had to (un)learn through this journey include:

1) how to actually learn in a way that fosters understanding rather than rote memorization, regurgitation, and then removal of said information from my brain. I have no tips and tricks for this, it involves a lot of reading and then often discussing what I’ve read, or even applying things to my own data. As much as I wish it were, it is not an easy or fast process for me.

2) CODING. From that one time I used R in my undergrad genetics class to now regularly analyzing genomic datasets and creating figures for published papers in R. I also learned how to use (and understand the output of) high-performance computing clusters because let me tell you, there is no way you can navigate contemporary genomics data without some hefty computing. I wish I had known to learn some sort of computing language as an undergrad, be it Python, R, or even Unix.

3) how to read (and subsequently write) a scientific paper in my field. Science has a nifty article for figuring out how best to read a paper. For the most part, I don’t read the entirety of the paper. There’s too much cool science and too little time (and, frankly, working brain cells). I generally read the abstract first, then I tend to at least skim the introduction before reading the discussion, making sure I go back to the figures as they are being discussed. I tend to skip the methods unless I am curious or explicitly need nitty-gritty details. Of course, if I am reviewing a paper I will read the whole thing so I can give as nuanced and excellent feedback as I can.

Some papers are fundamentally written in a way that allows more people to understand their findings and also grasp the implications of their work. There are many more papers out there where it feels like you have to climb your way through obtuse language to grasp even a kernel of their findings. I think there is a time and place for dense papers, such as for new methods, technical notes, or even in more niche journals where the audience is generally more specialized. In conservation biology, however, I think our work has the greatest potential impact when people can actually read and understand it since we are a crisis discipline.

4) science (especially in academia) is not as open, collaborative, or welcoming place as it should be. And this is coming from a cisgender, white woman from a middle-income background, which is a place of relative privilege. There is too much information stuck behind a paywall and too few people from marginalized backgrounds making it up through the ranks in science or holding the positions of power therein. This is slowly changing as more people are becoming fed up with the status quo. Hot-take incoming. Higher education in the US is broken; I believe that institutions of higher education can either teach the masses well or make money. They cannot, and should not do both. Hot-take out.

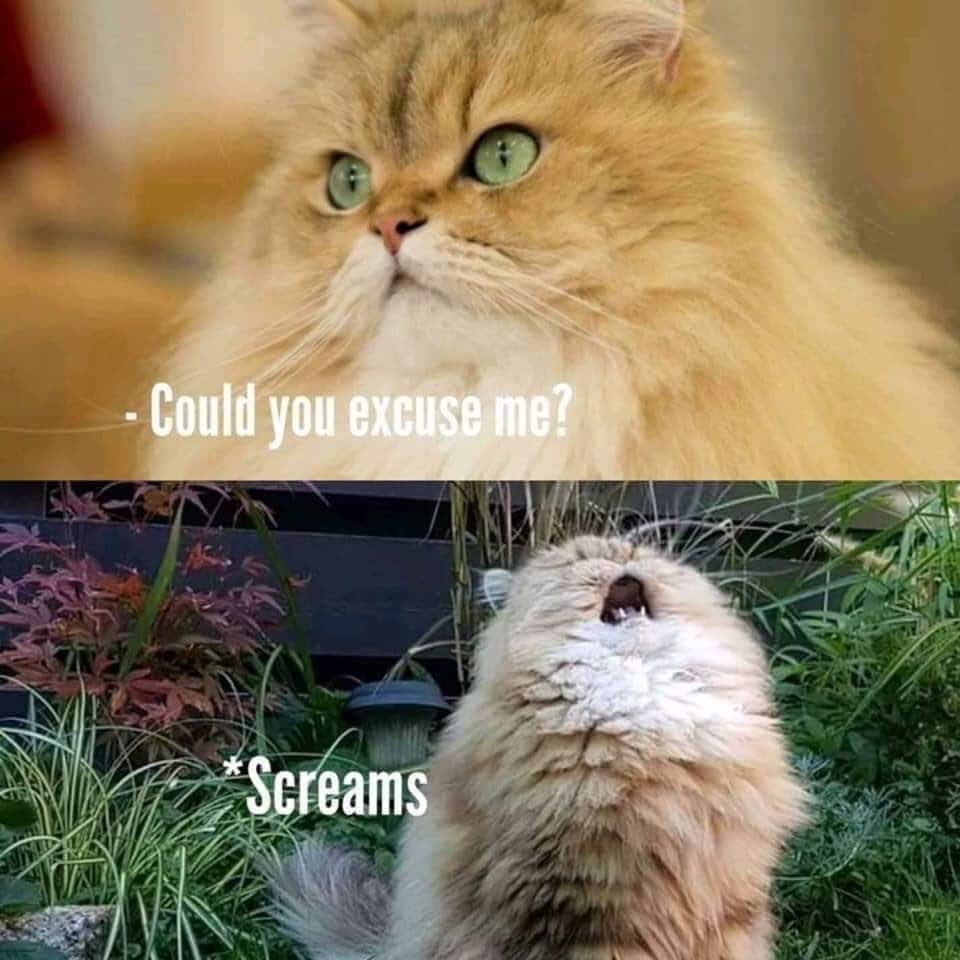

Those are all the thoughts/anecdotes I have for now. I hope to come back to this post later and add some more sources/thoughts/experiences, but for now, here’s my favorite meme.